|

Herbert Westfaling 1586-1601After his consecration as Bishop of Hereford on 30 January 1586, Westfaling became known for his zeal in confronting Roman Catholics and others whose religious practices he viewed as suspect, criticising Hereford's vicars choral for their use of "superstitious" images and pictures. He was also noted for the gravity and academic tone of his preaching. In 1592 he preached before Elizabeth I in the university church. Despite the Queen twice ordering him to cut his oration short to allow her to deliver a speech, Westfaling refused to be hurried and the Queen's speech was postponed until the next day. Westfaling was the author of a collection of sermons entitled A Treatise of Reformation in Religion, and also authored a number of poems in English and Latin, now in the library of the University of Cambridge. |

|

Francis Godwin 1617-1633Francis Godwin first came to prominence through his interest in historical and antiquarian studies.In 1590, he accompanied William Camden into Wales in search of antiquities for his revised edition of Britannia. Godwin’s most important work was A catalogue of the bishops of England, since the first planting of Christian religion in this island and the work led to his appointment as bishop of Llandaff in 1602. The work was translated into Latin and this achievement earned Godwin promotion to the wealthier see of Hereford in 1617.As a diocesan bishop, he was criticised for neglecting visitations – indeed he spent much time in his own writing, advocating the need for a definitive national history. The Man in the Moone is probably an early work, describing Gonsales, a Spaniard, who trains large swans or gansas, to carry an ‘engine’ to the moon, where he meets with all kinds of adventures. Godwin had far-sighted views on gravity and what it requires to launch a machine into space. He also discussed the motions of the planets, using views developed from those of Copernicus.Godwin died at the bishop of Hereford’s palace at Whitbourne and was buried in the chancel of the church there. |

|

George Coke 1636-1646George Coke was bishop of Hereford at a time of great crisis for the city and country. He moved to Hereford from Bristol where he had been bishop and probably owed his preferment to Archbishop William Laud. By all accounts his time at Hereford was not a happy one. He described the city in February 1640 as ‘this place of trial, under so much variety of business and among such men, as are too strong and cunning for me.’He estimated that among all the justices in the county, only four were his staunch supporters and he sensed a great deal of opposition. Added to this, he experienced personal and family difficulties – by 1637 his eyesight was failing, and in dim light he was forced to wear spectacles. In October 1638, he was censured by Archbishop Laud for presenting one who was insufficiently learned to a cathedral post. Apparently one of Coke’s sons had deserted his apprenticeship and had run away to sea, but seeing in the storms that battered his vessel a sign from heaven, he had turned back, and sought ordination. His indulgent father, Bishop Coke, made him precentor of Hereford Cathedral! Coke was certainly of the high church party and fought for all that the Church of England stood for. When, in 1641, a bill for excluding bishops from the House of Lords was passed by the Commons, twelve bishops, including Coke petitioned Parliament, for which he was impeached and imprisoned for seventeen weeks. Retiring to his see, he was in Hereford in April 1643 when it fell to Parliament, but, under the articles of surrender of the town, escaped further persecution. However, when Hereford fell for the second time, in December 1645, Coke was captured and taken to Gloucester and, in August 1646, he and other prisoners were taken to London. He was allowed to return to his house at Eardisley and died there. Coke was buried in Eardisley church and there is a cenotaph in his memory in the south-east transept of Hereford Cathedral. |

|

Nicholas Monck 1661Monck was consecrated as bishop of Hereford on 6 January 1661 but died in December, that same year and was buried in Westminster Abbey. It is said that he never visited his diocese. |

|

Herbert Croft 1662-1691Brought up as a Jesuit at Douai, Herbert Croft returned to the Anglican church under the influence of Bishop Morton of Durham. Ordained deacon and priest in 1638, he became dean of Hereford at the height of the Civil War in 1644. When the city was taken by Colonel Birch’s Roundheads, he preached bravely from the pulpit against sacrilege and wanton destruction – his pulpit still stands in the cathedral and a roundel showing the scene appears on the west front. During the Commonwealth, he was dispossessed but returned as bishop of Hereford at the Restoration of Charles II. He was a man of great piety, conscientious in his duties. A contemporary correspondent wrote that ‘the bishop hath won the hearts of all sorts of people, and yesterday at least five hundred persons came to be confirmed to their great joy and comfort’. He was generous – providing a weekly dole at the palace gate for 60 poor people. Although brought up a Roman Catholic, he dealt harshly with the Jesuit College at Cwm in the south of the diocese, confiscating its library – which is still in the possession of the cathedral. At the same time, he worked tirelessly to heal divisions among the Protestant churches and to encourage the return of nonconformists to the established church. His tomb-slab in the southeast transept is alongside that of his dean, George Benson. Engraved hands are joined,across the black slabs -a great symbol of friendship, with the inscription, ‘In vita coniuncti, in morte non divisi’ – ‘united in life, not divided by death’. |

|

Gilbert Ironside 1691-1701Ironside was Fellow, then Warden of Wadham College, Oxford, later becoming bishop of Bristol. He was not universally liked. A contemporary called his a ‘prating and proud coxcomb’ while another spoke of him as ‘forward, saucy, domineering, impudent and lascivious’. Another as ‘the roughest man I ever knew’. He died on 27 August 1701 and was buried in the chancel of St Mary Somerset church, in a silver coffin, so it was said. In 1867, the church was dismantled and the dead removed from the vaults. The remains of Bishop Ironside were found encased in lead, but with no trace of an outer silver coffin, which may have been stolen. By order of the burial board, the lead coffin was opened for identification of the body – this was so perfect that the skin was not broken. After identification, the lead was secured again and the coffin sent by rail to Hereford. On Christmas Eve, 1867, in the presence of the dean, archdeacon and precentor, the bishop’s remains were laid in a vault in the southeast transept of the cathedral. The original black marble slab from St Mary Somerset church marks the spot. |

|

Philip Bisse 1713-1721Philip Bisse established contacts that greatly advanced his career– a cousin of Robert Harley, earl of Oxford, he married Bridget Osborne, daughter of the first Duke of Leeds and widow of the Earl of Plymouth, an illegitimate son of Charles II. Described by Harley as ‘my urbane and socially-minded cousin, whose talents as a genial matchmaker for the aristocratic young were unsurpassed’, Bisse became bishop of St Davids and later, in 1713, bishop of Hereford – no doubt proposed by Harley in return for political support. He was a favourite of Queen Anne and many saw him as a likely successor to the archbishop of York, John Sharp, on his death in 1714. For all his political angling, Bisse was an exemplary diocesan bishop. He undertook his episcopal duties efficiently and with great care. His visitation articles were very thorough and he was a great supporter of diocesan charities. In particular, he supported his brother, Thomas, in his aim to make the fledgling Three Choirs Festival, into a significant means of support for poor clergy and their dependents. At a time when most bishops were enthroned using a proxy, Bisse attended in person and, also unusual for the time, conducted most of the ordinations in his own cathedral. He was a great supporter of Hereford Cathedral and made substantial alterations to the Quire, providing panelling, galleries for his family and prebendaries and a huge reredos, with realistically painted curtains with tassels. The central tower was causing anxiety, and Bisse ordered to supports to be inserted - these were ineffectual and actually weakened the structure by lateral pressure. On arrival in the diocese, he found the bishop’s palace ‘incommodious and unwholesome’ and practically rebuilt it at a cost of about £3,000 of his own money. He divided the great hall into five compartments and re-faced the walls with stone from the ruinous chapter house. |

|

John Butler 1788-1802A native of Hamburg in Germany, butler became a popular preacher in London and a political pamphlet-writer supporting Lord North, the prime minister, at the time of the American Revolution. He was well-connected, his second marriage being to a daughter of Sir Charles Vernon, of Farnham in Surrey. After a period as bishop of Oxford, he was translated to Hereford. He spent some of his time at Bath and there exists in the cathedral library, a charming collection of letters to his wife, in which he describes the delights of ‘the season’ in Bath. In 1802, Lord Nelson visited Hereford and the bishop wrote to him, regretting that he could not have him to stay at the Palace, due to his age and infirmity. He may well have had scruples of inviting Nelson to stay as he had Lady Hamilton accompanying him! |

|

Thomas Musgrave 1837-1847Musgrave studied at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he became Lord Almoner’s reader in Arabic. On becoming bishop of Hereford, he revived the office of rural dean and established the Diocesan Church Building Society. During his time, the cathedral underwent a major restoration, overseen by the dean, John Merewether and the architect Cottingham. Musgrave became archbishop of York in 1847 and died in London three years later, buried in Kensal Green cemetery. There is a full-length effigy of him on his memorial in York Minster. |

|

Renn Dickson Hampden 1848-1868Renn Dickson Hampden was, twice in his career, vilified for his perceived unorthodoxy. At Oxford, he was one of the Noetic theologians, insisting that scriptural revelation was rightly supplemented by evidence of divine dispensation in the natural world – and both were properly understood in the context of human reason. In 1834 he became professor of Moral Philosophy at Oxford and in 1836 was nominated by Melbourne as Regius Professor. This caused a storm of protest, not least from Pusey and other Oxford dons, who opposed his liberal views on the admission of dissenters to the University. The controversy marked the emergence of parties within the Church of England, separating high-churchmen from liberal Anglicans. In 1847, Lord John Russell offered Hampden the see of Hereford. Again, there was much protest and thirteen bishops remonstrated with the prime minister. At Hampden’s election as bishop, twelve prebendaries absented themselves and Dean John Merewether voted against the new appointment. When he arrived at Hereford, Hampden threw himself into his diocesan duties; he founded the Diocesan Education Society in 1849 and encouraged church building, also securing the reopening of the cathedral after its restoration. As he grew older, his orthodoxy became more pronounced and he was a critic of the liberal-minded book Essays and Reviews following its publication in 1861. Hampden died in London on 23 April 1868 and is buried in Kensal Green Cemetery. |

|

James Atlay 1868-1894After Cambridge and ordination, Atlay served in parish ministry in Nottinghamshire and near Cambridge, but it was as a tutor at his old college, St John’s, that he showed his particular skills as an educator of the young. This skill he extended in his next post as vicar of Leeds. Here, Atlay continued the distinguished ministry of his predecessor, Walter Hook, training many curates and running his parish with huge care and efficiency. In 1867 he refused the bishopric of Calcutta, but the following year he accepted Disraeli’s offer of the bishopric of Hereford, in succession to Renn Dickson Hampden. Atlay brought to the diocese the same thoroughness which had been so successful at Leeds and Cambridge. Except for his times of duty in the House of Lords, he rarely left the diocese but spent all his time focused on his clergy and their parishes. He is said to have visited every church in the diocese and certainly worked tirelessly for the improvement of clergy incomes and accommodation. Education was of great importance to him – he supported its extension in the diocese and was a great champion of girls’ schooling – an area often neglected in his rural diocese. His own family – he had eleven children – gave him a great sympathy for young people and Archbishop Benson summed up the views of both young and old when he described Atlay as ‘the most beautiful combination of enthusiasm, manliness and modesty’. He is buried in the Lady Arbour of Hereford Cathedral and there is a fine marble recumbent effigy of him in the north transept of the cathedral. |

|

John Percival 1895-1917A giant of the Victorian age. John Percival founded one public school (Clifton College) and reformed another (Rugby). He was head of an Oxford College (Trinity) and was an important supporter of the foundation of the University of Bristol, as well as being one of the founders and first President of Somerville College, Oxford. At first, he seemed an unlikely bishop of Hereford – a staunch supporter of temperance in a county of cider-makers – a liberal in a fiercely Tory county – a Protestant in a diocese with High Church leanings, and a known supporter of Welsh disestablishment. He was also a rather puritanical disciplinarian - a reformer and controversialist, and whether from the pulpit or in the press, castigated the forces of inertia and reaction. Some went so far as to say that he was ‘hated like a devil’. However, he proved a pastorally-hearted bishop - always enthusiastic about education (he founded the Workers’ Educational Association) and encouraging literacy in the parishes through his Circulating Book Boxes and through the giving of prizes in parish schools. At heart, however, his interests were more national than local – he chaired the 1897 Lambeth Conference’s committee on industrial problems and became increasingly involved in educational reform. There was also a deep loneliness – partly through the death of a son and of his first wife, partly as he felt out of the thick of national events in Hereford and partly through being passed over when the archbishopric of York became vacant in 1908. Percival died on 3 December and was buried in the crypt of the chapel at Clifton College, but he is remembered in Hereford by a fine marble plaque beneath the central tower. |

|

Herbert Hensley Henson 1918-1920When Lloyd George nominated Henson as bishop of Hereford in 1917, there was an immediate outcry because of his perceived heretical views. At his election, ten prebendaries absented themselves and the resulting unpleasantness caused Henson much grief - he looked back to the day of his consecration in Westminster Abbey – 2 February 1918- with some sadness. In fact, although he was a theological liberal, he was only concerned, as his biographer, Owen Chadwick states, ‘to restate the doctrines of the Church of England in such a way that they will not offend intelligent men’. He stood for the right of Christians to profess their faith, while remaining agnostic about miracles. When he came to Hereford, he was immediately seen as a pastoral bishop – the first to drive around his diocese in a motor car – one which, apparently, regularly broke down! After only two years at Hereford, Lloyd George, translated Henson to Durham, where he became a powerful voice, both locally and nationally. Here, he showed his strong opinion on all subjects – a critic on moral grounds, of the behaviour of the Trades Unions. While loved by ordinary people, he came into fierce controversy with the miners’ leaders. He strenuously defended the Establishment of the Church of England, and after the 1927 Prayer Book fiasco in Parliament, he became its most vocal assailant. |

|

Martin Linton Smith 1920-30Smith was born into a clerical family – his father was dean of St Davids. He was educated at Repton and Hertford College, Oxford. Ordained priest in 1894, he was a curate in four parishes before becoming an incumbent at Colchester in 1902, and later, a canon of Liverpool Cathedral. During the First World War, he gained the DSO for his bravery at The Somme, Arras and Ypres. After the war, he became bishop of Warrington and in 1920, was translated to Hereford. Finally, for nine years, he was bishop of Rochester. |

|

Charles Lisle Carr 1931- 1942Lisle Carr was educated at Liverpool College and St Catherine’s College, Cambridge, becoming a Fellow there in 1934. On ordination, he became curate in Birmingham diocese, and then at Redditch. Following a period as Tutor at Ridley Hall, Cambridge, he became vicar of St Nicholas, Blundellsands, Liverpool and then, also in Liverpool, Rector of Woolton. After a period as archdeacon of Norfolk and then of Norwich, he spent two years as Archdeacon of Sheffield before becoming bishop of Coventry in 1922. He was translated to Hereford in 1931. |

|

Richard Parsons 1941- 1948Parsons was born in 1882 and educated at Durham School and Magdalen College, Oxford. Ordained priest in 1907. He was a curate at Hampstead before serving four years as chaplain of University College, Oxford. He was Principal of Wells Theological College 1911-16. He served for one year as a Temporary Chaplain to the Forces. In 1927, he became bishop of Middleton and was one of several who made major contributions to the revision of the Book of Common Prayer, during the 1920s. Parsons was translated to Southwark in 1932 and to Hereford in 1941. |

|

Tom Longworth 1949-1961Born in 1891, he was educated at Shrewsbury and University College, Oxford and was ordained 1in 1916. From 1927 to 1935 he was rector of Guisborough and then Benwell before becoming bishop of Pontefract in 1939. He was translated to Hereford in 1949. During his term of office, in 1957, the cathedral and diocese were visited by HM The Queen and HRH the Duke of Edinburgh. |

|

Mark Hodson 1961-1973Born in 1907, Hodson was educated at University College, Oxford and began his career with a curacy at St Dunstan, Stepney, after which he was Missioner at St Nicholas Perivale and them Rector of Poplar in the East End. In 1955 he was appointed suffragan bishop of Taunton, being translated to Hereford in 1961. |

|

John Eastaugh 1974-1990Born in 1920, John Eastaugh was educated at the University of Leeds and was ordained in 1944. After a curacy at All Saints, Poplar, he held incumbencies at Hackney and Heston in the diocese of London before becoming Archdeacon of Middlesex in 1966. He was consecrated bishop of Hereford in 1974 and served for 16 years before he died in office in 1990. |

|

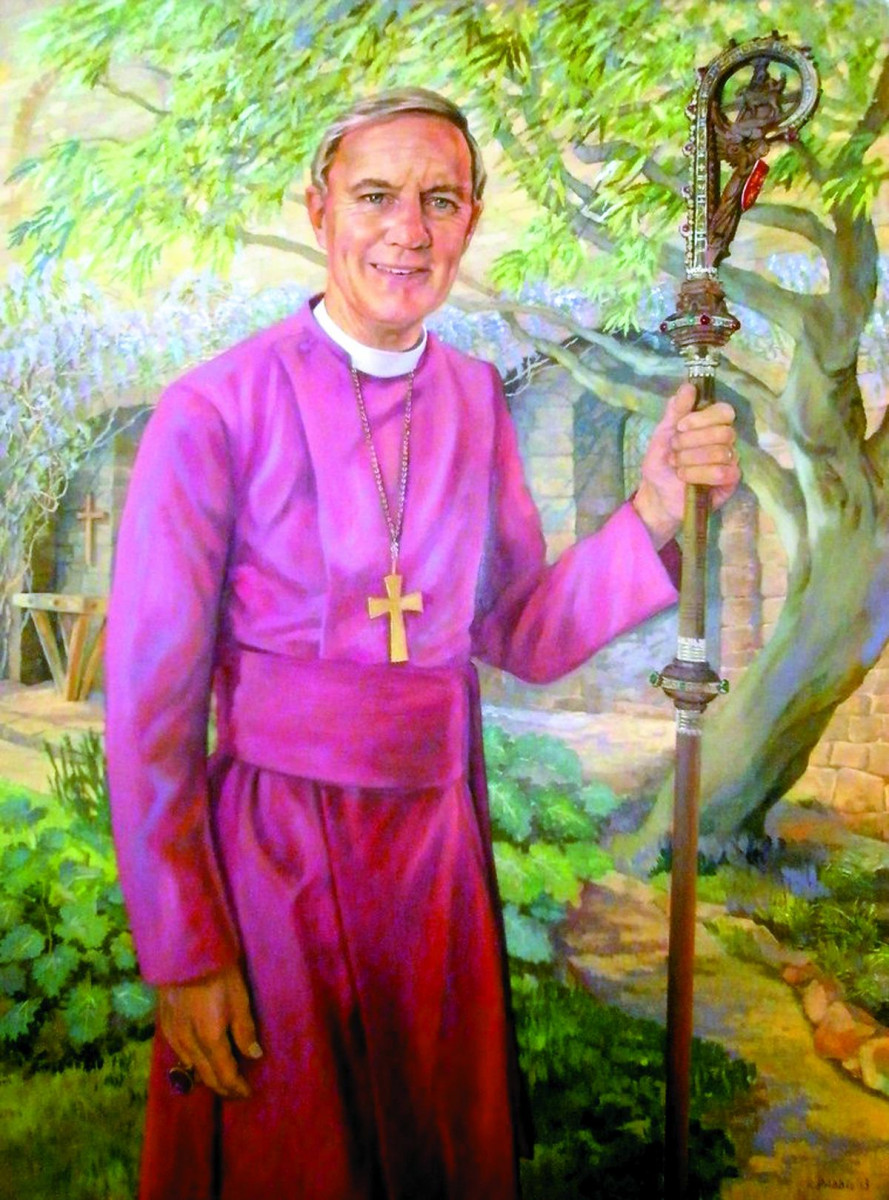

John Oliver 1990 - 2003Born in 1935, John Oliver was educated at Westminster and Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. He has Master of Arts (MA Cantab) and Master of Letters (MLitt) degrees. He was made a deacon in 1964 at Cromer Parish Church and ordained a priest the Michaelmas following at Norwich Cathedral, both times by Launcelot Fleming, Bishop of Norwich. After a curacy in Norfolk, he spent a period as chaplain and assistant master at Eton College. Following incumbencies in Devon, he became Archdeacon of Sherborne and Rector of West Stafford in Dorset before being consecrated as a bishop on 6 December 1990 at Westminster Abbey. He served in the House of Lords from January 1997 until November 2003 with special responsibility for agricultural and environmental policy.

|

|

Anthony Priddis 2004-2013Born in 1948, Anthony Priddis was educated at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, New College Oxford and trained for the ministry at Cuddesdon. After a curacy in the diocese of Canterbury, he became chaplain of Christchurch, Oxford, then Team Vicar in high Wycombe. From 1986-96, he served as Rector of Amersham and was an honorary canon of Christchurch, Oxford. In 1996, Anthony was consecrated Bishop of Warwick and in 2004 he was translated to Hereford, from where he retired in 2013. |

|

Richard Frith 2014-2019Born in 1949, Richard Frith was educated at Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge and trained for the ministry at St John’s College, Nottingham. After a curacy in the diocese of Southwark, he became Team Vicar of Thamesmead. From 1983-92, he served as Team Rector of Keynsham in the diocese of Bath and Wells and was a prebendary of Wells Cathedral. In 1992, Richard became archdeacon of Taunton and was consecrated bishop of Hull in 1998. In 2014, he was translated to Hereford, from where he retired in 2019. |